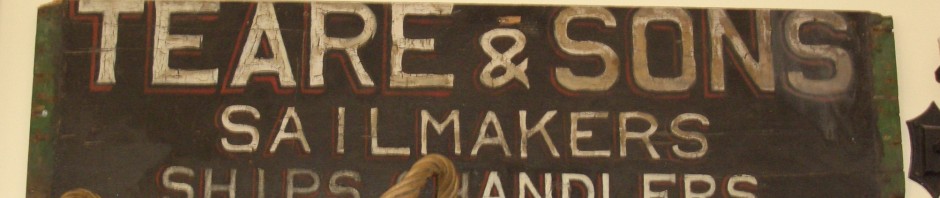

Frederick Teare was born in Peel the oldest son of William Edward Teare master sail maker and partner in Teare and Sons ships chandlers. He was 5ft 5in with brown eyes and hair and aged 37 at the start of WW1 when he was working in Rangoon, Burma – a river pilot bringing boats into port. Letters to home told the story of how his remarkable coolness resulted in the singlehanded capture of a German steamship. I first heard the story from his nephew Ken Teare and you can also find it in ‘This terrible ordeal’ Matthew Richardson’s excellent book about Manx involvement in WW1.

Frederick Teare was born in Peel the oldest son of William Edward Teare master sail maker and partner in Teare and Sons ships chandlers. He was 5ft 5in with brown eyes and hair and aged 37 at the start of WW1 when he was working in Rangoon, Burma – a river pilot bringing boats into port. Letters to home told the story of how his remarkable coolness resulted in the singlehanded capture of a German steamship. I first heard the story from his nephew Ken Teare and you can also find it in ‘This terrible ordeal’ Matthew Richardson’s excellent book about Manx involvement in WW1.

Apparently Frederick had always wanted to go to sea and despite a poor report on his mathematics from Patrick School he finished his schooling at Old Douglas Grammar School before realizing his ambition and he got his Captain’s ticket in 1904. He started his sailing career in 1893 with a 4 year apprenticeship on the four masted sailing barque Andelana out of Liverpool and then served another year after becoming an AB (able seaman). A brief spell in the RNR (Royal Naval Reserve) aboard HMS Collosus, a second class battleship built in1882 and at that time a coastguard ship based out of Holyhead was followed by 2nd mate positions on the French steamer La Madeleine and the Liverpool barque Mashona. He became 1st mate on the 1196 ton square rigger Robert Duncan out of Greenock in 1902.

He continued serving in deep water vessels and at the start of WW1, one hundred years ago, Frederick was a pilot aboard the fast coasting steamer, Hindu, which would meet vessels wanting to be taken up the Irrawaddy River to Rangoon (now Yangon and the former capital city of Myanmar). Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, following an “unsatisfactory reply” to the British ultimatum that Belgium must be kept neutral. The Rangoon port authorities had already been informed that the large Hamburg- America Cargo Liner, Alesia, had passed through the Suez Canal on July 26th, destination Rangoon. According to Lloyds register she was fitted with wireless and with war declared everyone assumed she would head for a neutral port. So imagine the surprise and consternation when Captain Teare was called on deck by the lookout during a blinding squall to see a large boat flying the German flag passing under the stern of the pilot boat – it was the Alesia. There were many questions – What were her intentions? Was she armed? Did she intend to attack Rangoon port? And then a sharp eyed lookout noticed there was no wireless gear aloft . . . .

Frederick Teare was the pilot on duty and he had an ability not only to remain calm but also to conceal any facial expression, which he used to his advantage. He packed his bag, leaving behind his copy of Field Service Regulations from his membership of the Rangoon Volunteer Rifles, and took the small boat to board the Alesia. On his way he scanned the decks and faces of the crew and the bearded captain to find any clues. When he got on board the captain asked him ‘So what about the war’ and Frederick bluffed that ‘It had fizzled out’. The captain left the bridge and Frederick was left with the 2nd officer on the bridge wondering if the Captain was also bluffing. When the Chief Officer came onto the bridge he also asked about the war and Frederick took his chance and suggested that ‘If the wireless was in good order they’d have as much news as him’. The reply confirmed that the radio had been dismantled for repairs and that had been very inconvenient.

Frederick could find no reason to believe this wasn’t true so he took the Alesia up river, past the military installation at Elephant Point where there was much activity and which he passed off as the annual military manoeuvres. They moved up river and anchored for the night then at the first streak of dawn the first officer reported there was a large launch alongside and soon Frederick saw two platoons of Royal Munster Fusiliers coming on board. The German Captain raged at him ‘What does this mean Pilot? to which Frederick coolly replied ‘I am sorry to say Captain that our countries are at war and I have captured your ship’.

One of the first maritime actions of the war and certainly the first to involve a Manxman was any other ship ever captured with so much cool and daring by just one man? Official reports of the time described Frederick Teare as a man ‘typical of the British officers bred by our tramp steamers’. The Alesia was subsequently offered for sale in the London Gazette as a prize along with other captured German merchantmen and was purchased by the Government of India.

Frederick Teare left Burma in 1915 with the Burma military contingent; he became a sergeant in the 2nd battalion Seaforth Highlanders (Lewis Gun Section). He was posted to France in April 1915 and would have taken part in the Second Ypres battle and on the Somme when the 2nd battalion Seaforth Highlanders attacked on Redan Ridge 1 July 1916 and near Le Transloy in October 1916. He was twice wounded during this time.

During the battle of Arras (the First Battle of the Scarpe), which ran from 9 – 14 April 1917, there was a disastrous action involving the 4th Division on the Green Line from Fampoux. At midday on the 11th April the 2nd Seaforth Highlanders and 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers attacked from the sunken lane between Fampoux and Gavrelle . They were spotted whilst forming up by the enemy in Roeux and on the railway embankment and subjected to shellfire. At zero hour, as they advanced over a kilometre of open ground behind a feeble artillery barrage they were hit by heavy machine gun fire from the railway embankment and Chemical Works. The Seaforths attacked with 12 officers and 420 men and suffered casualties of all 12 officers and 363 men. Only 57 men survived this attack unwounded. They were withdrawn from the line on 13th April. This action and the casualties from other battalions of Seaforths are commemorated with the Seaforths Cross at Fampoux. Frederick Teare was wounded leading his platoon in this action and died of his wounds in no 26 military hospital on 23 April 1917 aged 40 years. He is buried in Etaples military cemetery and his name is recorded on the Peel War memorial.

Frederick’s brother Frank Teare served in the Canadian Army and was killed on the 10 April 1917 in the attack on Vimy Ridge just a few miles from Fampoux.

Back to WW1 Teare memorial page

More on Seaforth Highlanders and battle of Arras at http://jeremybanning.co.uk/tag/seaforth-highlanders/

Memorial to Seaforth Highlanders, Fampoux http://www.ww1cemeteries.com/othercemeteries/seaforth_highlanders_memorial.htm